Instruments of Peace

Can the arts save the world? These local artists, leaders of a movement for peace and understanding, believe they can.

December 17, 2021 Rick Broussard | Reprinted with permission

The world today seems critically poised between two opposing destinies. Optimists picture one of unlimited human progress, driven by science breakthroughs for cheap energy, abundant food production, and the elimination of disease and even aging. Pessimists imagine a future of global comeuppance as our excesses of consumption and pollution spark environmental catastrophes and rouse deep-seated rivalries until we descend into a new Dark Age.

Surrounded by a world of instruments, Randy Armstrong demonstrates a couple of his favorites: a 1948 Gibson L7 Archtop guitar (above) and a handmade Radha Krishna Sharma sitar (below left). Photo by Kendal J. Bush

Either view can be a call to purposeful action or to dour resignation, but there is a third approach to our global destiny that sees, in the tragic and comic waves of events, an inspiration to create something entirely new. This approach applies the simple grace of song, dance, poetry and art to give life meaning and joy, to elevate humanity, and perhaps even save it from the forces of death, doom and destruction.

Indeed, even the Dark Ages themselves are remembered for breakout appearances of some of the world’s greatest works of art, like the Book of Kells in Europe as well as the lustrous beauties of the Byzantine Empire and the beginnings of the Golden Age of Islam in the Middle East.

Randy Armstrong with a handmade Radha Krishna Sharma sitar from Kokata, India. Photo by Kendal J. Bush

But the Renaissance era of art and music that followed the Middle Ages never really ended and that hopeful surge of human achievement, civilization and creativity extends all the way to New Hampshire’s contemporary galleries, theaters and music halls.

As Editor of this magazine for about 30 years, I have more than passing familiarity with arts in the Granite State, so it was as a personal search for some hopeful news that I sought one of the original leaders of an artistic movement for positivity, peace and understanding. known as “world music.”

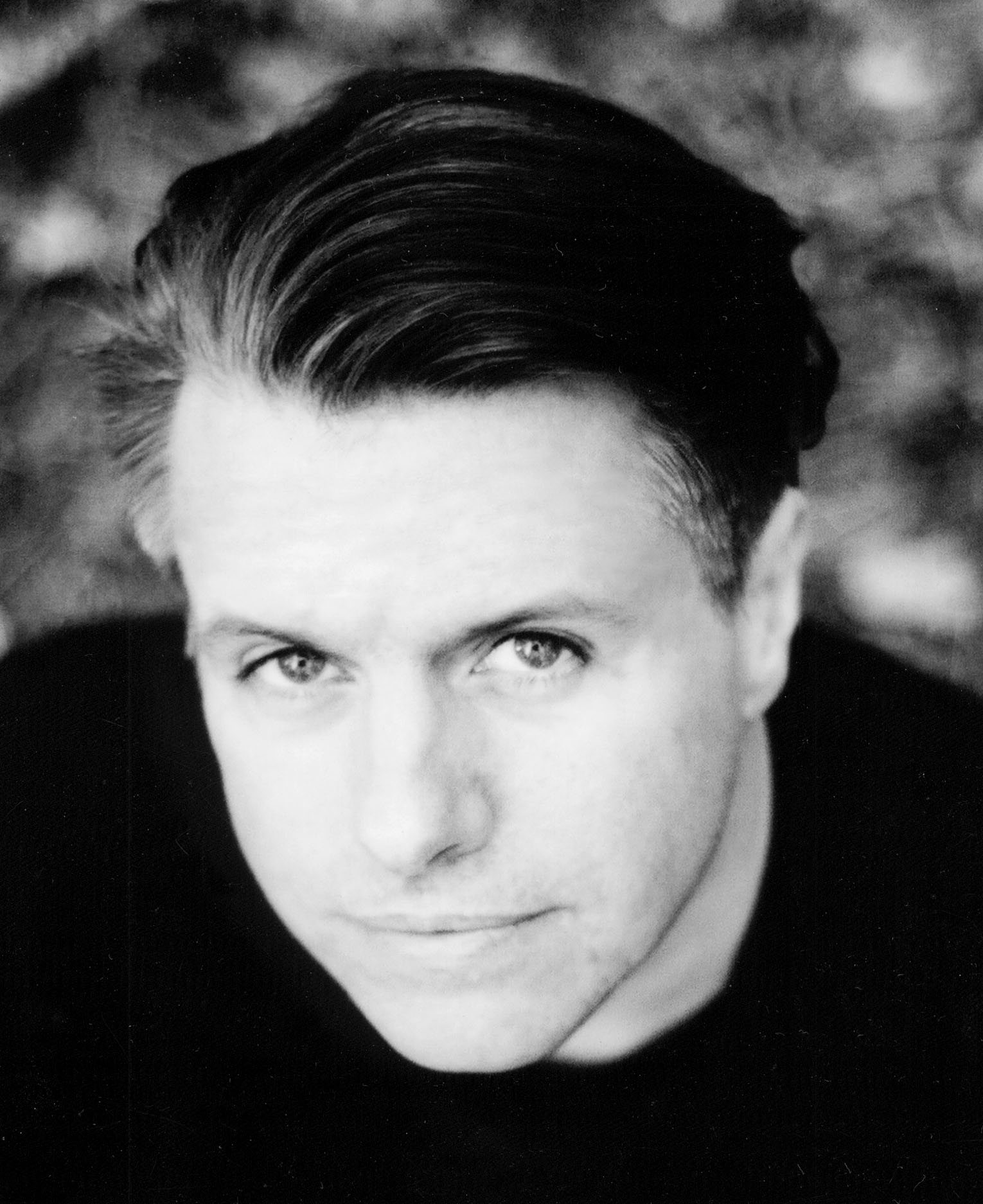

I’ve known of Randy Armstrong for almost as long as I’ve lived in New Hampshire. I’ve reported on his successes and reviewed samples from his vast catalog from time to time, so it almost came a surprise to realize that we had never met.

Armstrong was a bit giddy upon my arrival at his home deep in the hills of Barrington. Just moments before, he had received notice of the birth of a new grandchild. “They told me I’m a randfather!” he says with a huge smile, enjoying the play on his first name. Randy Armstrong smiles a lot and projects warmth and positivity as he shows me around his home that doubles as a recording studio and triples as a place to keep and display his hundreds of musical instruments from around the world. He can play them all: sitars, ouds, wooden flutes, exotic drums like djembes, and an array of kalimbas and mbiras rustically crafted from boxes or gourds with toned keys to be played with thumb or forefinger.

The furniture in his well-appointed parlor has been pushed aside to host a half-dozen marimbas, like large wooden xylophones in various keys, custom made for him in South Africa. Armstrong says he was compelled to order them after watching Bishop Desmond Tutu break into dancing when a marimba band with a similar set played during a visit to that nation years before.

Armstrong cites many such inspirations, but it’s curious to hear that one of his heroes of global awareness was a distant relative most famous for setting foot on the moon: Neil Armstrong. “We’re both Scottish, from the same clan,” he says. The experience — shared with all us Earthlings — of the Apollo crew looking back on the Earth as a blue marble floating on the black velvet of space, transformed his thinking. It was 1969, just a year after the assassination of Martin Luther King while the Vietnam War still raged. He was an aspiring rock star who had begun listening to international touring artists like Babatunde Olatunji, sharing the wisdom, rhythms and cultures of Africa, and his mind opened to the possibilities of a wider world of music.

“I went out and bought my first sitar and djembe,” he says, “and then I got my first record contract. I was in my early 20s.” That contract with Philo Records gave his new band, Do’a, featuring partner, friend and flutist Ken LaRoche, the kind of legitimacy that attracted serious music reviews. Jazz legend Dizzy Gillespie endorsed their first album, “Light Upon Light,” as “one of the important contributions to the future of music.”

Four more albums with Do’a followed, expanding into and shaping the trends of world fusion and new age music that were suddenly finding their own bins in music stores. The band’s “Companions of the Crimson Coloured Ark” even came with a mission statement:

“It is our hope that the music produced on this album will contribute in some small way to the cessation of human suffering, and to the realization of the unity of the human race and the need for the elimination of all forms of prejudice.”

Performing as Do’a World Music Ensemble, the band’s last album, “World Dance,” made it into the top 10 on the Billboard New Age Music Chart.

Armstrong’s next band project, “Unu Mondo” (Esperanto for “one world”), furthered a musical partnership with composer and bassist Volker Nahrmann that continues to this day. In 1999, Armstrong was commissioned to score and record the original soundtrack for a four-part PBS series, “Dinner on the Diner,” that was filmed in South Africa, Spain, Scotland and Southeast Asia. He says the gig required some stretching of even his eclectic instrumental skills to perform the music of Thailand, weaving traditions from China, India and Cambodia.

Along with his global travels and intersections, Armstrong has been busy much closer to home, teaching sitar and tabla to students at Phillips Exeter Academy and graduate courses at Plymouth State University. A long-time friendship with Genevieve Aichele, founder of the New Hampshire Theatre Project, blossomed into “World Tales,” a theatre, storytelling and music production designed to provide cross-cultural experiences to young people. “Gen is such a deep thinker and passionate human being. We’ve been friends and collaborators for about 30 years now,” he says. The efforts resulted in two “World Tales” albums and an award-winning residency partnership that, along with so many projects, is on hiatus as a result of the pandemic.

Theo Martey with friends — for more about his traditional dancing and drumming, visit akwaabaensemble.com

While serving on the New Hampshire State Council on the Arts for nine years, Armstrong’s mantra was, “We must infuse the state with arts from younger people.” The consistent focus bore fruit, he says, “and those people are leaders now.” And many are also collaborators with Armstrong, like Sarah Duclos, a Seacoast dancer and choreographer who uses dance to tell stories of community, and West African drummer Theo Martey of Manchester (by way of Ghana).

Armstrong was leading a workshop on African drumming at the Boys and Girls Club when Martey showed up at one of the classes and sat in. Armstrong quickly realized that he was outmatched. “I never considered myself an African drumming master, although I can play,” he says. Soon a deep friendship began. “I’m godfather of his children,” says Armstrong. Now Martey directs his Akwaaba Ensemble, performing for events and teaching African drumming and culture to New Hampshire schoolkids. He’s in Armstrong’s latest band, Beyond Borders, whose eponymous 2015 record was nominated as Best World Album at the ZMR Music Awards.

Beyond Borders may be Armstrong’s most ambitious undertaking. He describes it as a magnum opus reflecting four decades of touring, recording and performing. It features his partner Nahrmann and about 20 other exemplary musicians on a recording filled with tributes to heroes of cross-cultural musical innovation, including Dizzy Gillespie, Ravi Shankar and George Harrison.

The new band’s performances this year have been limited by Covid, but tickets are already selling for a show at the Historic Music Hall in Portsmouth in April.

In short, “Beyond Borders” is yet another work aimed at fulfilling Armstrong’s long-ago published goal of creating music that will “contribute in some small way to the cessation of human suffering, and to the realization of the unity of the human race.” His intent since those early days of Do’a has been constant, and Armstrong’s confidence in the power of music to do just that has not swayed.

“Most music and art come from some very deep and organic thing that happens within a culture, influenced by the great revelations of holy thinkers,” he says. A beneficial influence results, he says, “until humankind gets in there and screws it up, and that’s where we get all the conflicts.” But what art and music have begun, art and music can complete, he says. We just have to appreciate how far we’ve come. “If you look at all these prophets and amazing leaders of religion and science, they all point to the same place.” It’s a place of unity where all are respected and no one is left out, he says, and we have to remember to keep reaching for it and believe it’s within our grasp.

Artist of Change: Theo Martey

Artist of Change: Theo Martey

“Music has a different power. It moves in people a different way than science or politics. It unites us physically as well as mentally.”

Theo Martey began performing at age 6. By 17, he was working with the most acclaimed performance ensembles in his native Ghana, West Africa, and earning a reputation as an engaging dancer, drummer and choreographer. In 2002, he created the Akwaaba Ensemble, and has since dazzled concert audiences throughout the Northeast, Mexico and Canada. Along with many other appearances, he has performed with the Manchester Choral Society for their Zulu Mass and Christmas Tapestry project, and with the New Hampshire Theatre Project for the “Dreaming Again” production. He’s collaborated with Randy Armstrong on numerous projects, including the latest “Beyond Borders” album and global peace initiative. But his influence may be most powerful in his school workshops and residencies. “Young people are open. It sticks with them for a very long time,” says Martey. “Over the years, I’m feeling all the power of music to bind and bring people together,” he says. “Politics has a more divisionary angle with decisions on cutting funding and such because music and politics doesn’t tally. Music makes people feel like they are all together.”

At its worst, the conflict between actors on the world stage results in a kind of hell that we simply call “isolation.” The more that storytelling becomes the tool of those forces of division, the more that music and design and rhyme are molded to tease us apart, the more isolated we become.

At its best, the art we create and enjoy stimulates an awareness of the essential unity and potential greatness of humanity that overcomes the deceptions of our fight-or-flight-focused senses. In the greater scheme of things, there is hope for us all, he says, if we can still create and believe. “Even my drummer who is an atheist, I know he believes in something.”

Many of Armstrong’s personal beliefs find root in the Bahá’í Faith, the practice of which he learned from the musicians, Seals & Crofts (who hit it big with their feel-good record “Summer Breeze” in 1972). Dash Crofts sang on Armstrong’s tribute to Rev. Martin Luther King’s “I Have A Dream” that appears on the first Unu Mondo album, “Hand in Hand.”

Bahá’í, established in Persia in 1863, maintains a remarkably contemporary set of values including the essential value of all religions, a harmony of religion and science, gender equality, and the elimination of every prejudice, abolition of extremes of poverty and wealth and human rights for all human beings. While numbers of Bahá’í Faith members are small compared to Christianity, it has spread to all corners of the globe and places of worship are not hard to find. There’s even one in Dublin, New Hampshire, situated in the Historic Dublin Inn, where the Abdu’l-Bahá, eldest son of the founder, once visited and spoke.

It’s now something of a shrine to the faithful.

“The arts are a kind of sacrament for the Bahá’í,” Armstrong explains, and Abdu’l-Bahá described music as “the ladder of the soul.” Found in Abdu’l-Bahá’s writings in this:

“The art of music must be brought to the highest stage of development, for this is one of the most wonderful arts and in this glorious age of the Lord of Unity it is highly essential to gain its mastery.”

For a consummate musician like Randy Armstrong, the appeal is clear. His talent, mastery and spiritual quest converge, enabling him to share the sources of his inspiration with millions through his recordings and performances.

As I prepared to leave, Armstrong apologized and pulled his phone from a pocket. He said it had been buzzing while we spoke and he had an idea of why. He turned the phone to share with me his first look at a photo: a perfect baby girl with pink skin and a look of sublime wisdom and peace on her face.

“Her name is Oona,” said the proud “randfather.”

I didn’t ask at the time, but I looked up the meaning of the name when I got back to my laptop. For Scots like Armstrong, the word “oona” means “lamb.” Those same syllables in Spanish mean “number one” and in Latin would translate as “unique.” All fine portents for a precious new human being.

Artist of Change: Sarah Duclos

Artist of Change: Sarah Duclos

“I get excited for projects where I learn something from my community and use that as a conversation starter. Artists are good at starting conversations.”

“Hi, my name is Sarah and I am a recovering dance snob,” writes Sarah Duclos on her blog. Once a student of ballet and dance in a conservatory setting, she says, “Ballet, rightly so, comes from history of aristocracy, with dancers on stage and audience in seats, a hierarchic form of art.” But a transformative experience with a visionary choreographer during her tween years changed everything. “Liz Lurman was in Portsmouth and I got to dance with her. It was the first time I’d ever seen how dance could tell the story of a community: history, industry, first accounts — a docu-drama kind of dance.” She set out to discover what dancers can do when embedded in communities, eventually working with Randy Armstrong and other local artists to stage “Shelter.” This multimedia performance, staged in 2018 as part of the One Billion Rising events, raised awareness and funds for the work of Haven, which provides shelter for women escaping violence.

I pondered all of this on my way home from Barrington. The faithful of my own Christian faith sometimes are far less enthusiastic than Bahá’í about the unity of religions and as art as a positive spiritual influence beyond hymns, icons and stained glass. But from the vaulting lines and detailed crafting of the Gothic cathedral to the classic works of Renaissance devotional art to today’s more-emotional praise and worship under dramatic lighting on the evangelical stage — all express the sacramental nature of art and draw the faithful into fellowship.

I’m still optimistic by nature. I can’t help but feel confident that no matter what new horror is waiting around the bend — even after a couple of years of intense horribleness — it’s all going to be OK in the end. The problem with such optimism is that it’s not clear there is an “end.” After all, our troubled world just keeps spinning, no matter what messes we humans have gotten ourselves into or out of.

The Beatles — supreme bards of my generation of baby boomers — had a bright idea about it (and so many other things) and wrote a song titled, appropriately, “The End.” It was the last song they recorded as a foursome and each of them perform an instrumental solo in it (including Ringo’s only-ever drum solo), but what most fans remember best is the haunting, instructive, ultimate line:

“And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

Other artists come to mind for their statements that seem to demand a change in the hearts and minds of their audiences. Bob Marley’s peaceful militancy, touring a war-torn world on behalf of “One Love” is an example. The transcendental ordinariness of Thornton Wilder’s play “Our Town” (detailed beautifully by P.J. O’Rourke in our November issue) is a Zen knock upside the head that still draws a crowd to every local theater that stages it. Picasso’s monumental painting Guernica, depicting the bombing of the Basque town whose name it bears, has a way of conveying the horror of battle that transcends that of even the best war-time photography. Millions have grooved to the sweet sounds of Marley, pondered the funeral scene of “Our Town,” and contemplated the terrors of Guernica through the lens of art.

Experience Randy Armstrong

January 21

ETC Integrated Arts Conference

Building Community Through the Arts

Randy Armstrong, workshop leader

Plymouth State University – The Common Man Inn

For registration and info: campus.plymouth.edu/etc/integrated-arts-conference

April 9

“Beyond Borders” with Randy Armstrong & Volker Nahrmann in Concert

The Historic Theater at The Music Hall Portsmouth, 8 p.m.

Info: randyarmstrong.com

Tickets: themusichall.org

But is the world a better place for it all?

A year after John Lennon sang (and Yoko Ono screeched) through their recording of “Give Peace a Chance” in 1969, the war in Vietnam did end. Of course, history suggests that end was more the result of the ever-practical Richard Nixon knowing that the success of his new presidency hinged on fulfilling his campaign promise to draw the conflict to a close — no matter what awful final images the departure would leave on the retinas of history.

But would Nixon have found it “practical” to end such a struggle at great political cost if not for the array of multicolor, sometimes absurd, often objectionable but always entertaining acts of art that kept the war at the center of our conversations in ways that challenged the “official” story?

And, for all the concern for world peace and harmony, what if we are setting our sights a bit too close to home? Recent revelations about those odd moving lights in the sky that sometimes dazzle, baffle (and maybe even guide) the citizens of Earth have forced both scientists and politicians to think bigger about our place in the universe and our role in the cosmic drama of creation.

So consider this fact. When Carl Sagan, one of the most famous popularizers of science of the 20th century, was heading a committee charged with creating a “cosmic greeting card” to accompany the Voyager space flights through our planetary system and beyond, they chose the most reliable medium imaginable at the time (or now). It was a set of gold-plated copper discs — essentially 12-inch, 33 1/3 rpm record albums — containing digitized facts of science and sounds of Earth. Among the offerings prepared for the trip was a range of human voices and a recorded greeting from Kurt Waldheim, then-secretary general of the United Nations.

All of that was able to fit on one side of the two-disc package. In a letter to musicologist Alan Lomax — whose work discovering the native, authentic music of people outside of the star-making entertainment world is credited with helping to birth the world music movement — Sagan wrote: “The other three sides are devoted entirely to music — music representative of all of humanity and music which represents the best of humanity.”

The more than 300 instruments collected by Randy Armstrong during his tours and travels have all but filled his Beauty Hill Studios (seen here) and home in Barrington. Photo by Kendal J. Bush

Sagan asked Lomax to serve on the final music selection committee, noting the same albums of music would be published and shared to provide listeners a chance to “imagine how we want to be represented to the Cosmos.” (Sagan capitalized the word.) “In addition, it may be for many people a first exposure to some of the diversity and quality of human music.”

The Voyager flights are still out there, currently more than 14 billion miles from the sun carrying their bundles of 44-year-old technology and their payload of music and news from our tiny blue planet. But there’s no rush and no ETA for Voyager as it plods through infinite space at about 40,000 mph.

“Under its protective cover the flight record will have a probably lifetime of a billion years,” wrote Sagan. “It is unlikely that many other artifacts of humanity will survive for so prodigious a period of time.”

So, there’s indeed a chance, however slight, that these records of Earth will be found in some distant eon and discover a new audience among the stars, but what will those alien “ears” think of us? The science and facts on one side of the golden discs might be seen as too primitive (or dangerous) to be of much interest, but what of the other three musical sides? How might extraterrestrial beings react or, in the reaches of infinite time, respond?

“Who knows?” is a fair answer. The poetry of reggae prophet Bob Marley puts a more positive spin on the matter with words that also constitute a simple statement about the power of all art in its purest form. “One good thing about music,” sang Marley. “When it hits you, you feel no pain.”